Turnbull’s NBN Legacy of Failure

Malcolm Turnbull has left Australia with quite a legacy with the National Broadband Network (NBN).

Back when the NBN was first mooted in 2008 – (though one could argue its origins go back the OPEL Networks plan from 2006) – everyone was supposed to be on one of three different technologies – 93% of the population with Fibre-to-the-Premise (FTTP, with up to 100Mbps), 4% with Fixed Wireless (FW, with up to 25Mbps), and 3% Satellite Broadband (SB, with up to 12Mbps).

![Tmthetom [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]](https://michaelwyres.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/broadband-2019.jpg)

When then Communications Minister Stephen Conroy cancelled the OPEL plan in 2008, what has become known as the NBN was formulated, with the 93/4/3% split described above.

Enough capacity was to be put into the ground in the FTTP footprint to support 6 separate services – (4 data, and 2 voice) – in every single premise in those areas. The fibre going into the ground was to support services of up to 40Gbps.

To achieve those speeds – (over and above the standard 100Mbps offered initially) – all that would be required is an update to the electronics at each of the fibre connection.

Yes – the original 2008 NBN plan would have allowed for 40Gbps, dependent on CVC and backhaul capacity to be provided by individual ISPs.

Leading up to the 2013 election – and the change of government – then opposition communications spokesweasel, Malcolm Turnbull, and opposition leader Tony Abbott had other ideas.

Simply to oppose on politically ideological grounds, they decided that Conroy’s plan was “too expensive”, and would take “too long”.

Their alternative was to be “cheaper” and “faster to deliver” – neither which has been proven, and has in fact been widely debunked. Their plan called for all areas in which FTTP had not already been deployed, to change to Fibre-to-the-Node (FTTN, with up to 100Mbps), using existing copper.

The status of the existing copper was questionable at best.

The rollout has proven to be no faster to deliver – (and in fact has taken longer) – and sustainable speeds of 100Mbps have been so difficult to reach that most ISPs no longer even offer 100Mbps plans – including on the parts of the network that are deployed with FTTP.

What we in fact end up with is what Turnbull called the “Multi Technology Mix” (MTM) – which would leave Australia covered with FTTP in areas where it had already been rolled out, Hybrid Fibre Coaxial (HFC) cable in areas where HFC was already rolled out, FTTN in the remaining areas where FTTP had not already been committed and there wasn’t already HFC, and finally FW and SB in much the same areas as originally planned.

The FTTN areas were later broken up further to include some Fibre-to-the-Curb (FTTC) deployments when they realised FTTN, in particular, wasn’t cutting it. Many areas which they earmarked for existing HFC later switched back to FTTN or FTTC, because many of the existing HFC networks they purchased couldn’t be made suitable.

And 100Mbps? Not even remotely likely unless you’re in an FTTP area, and with an ISP that has purchased enough CVC and backhaul capacity.

Rare.

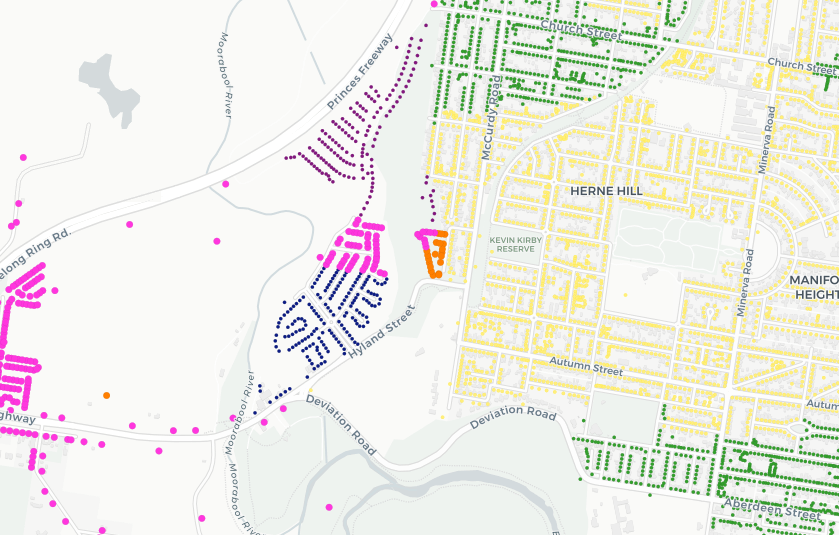

So what does the MTM end up looking like? Take a look at this small area in the western part of Geelong, Victoria, with mapping provided by NBN MTM Alpha:

The purple dots represent locations that are serviced by FTTP; the yellow dots locations that are serviced by FTTN; the green dots locations that are serviced by FTTC; the pink dots locations that are serviced by FW; the orange dots locations serviced by SB; and finally the blue dots locations that are serviced by fibre from a non-NBN provider.

This is pretty stunning – and stunningly stupid.

You’ll see in the bottom right a patch of FTTC – (green) – where some premises right next door to green dots are getting FTTN – (yellow).

In the same street.

In the middle of the map, you’ll see the hamlet of Fyansford – where at the southern end of town you have a non-NBN fibre provider – (blue) – and at the northern end of town you have FTTP – (purple) – with a blob of FIXED WIRELESS in between. This band of fixed wireless is about 10 house blocks wide – or around 120 metres.

Apparently nobody thought that this area – (which is the newest part of that residential estate) – right next door to two fibre areas should get any kind of fixed-line service – not even FTTN or FTTC.

Stupidity.

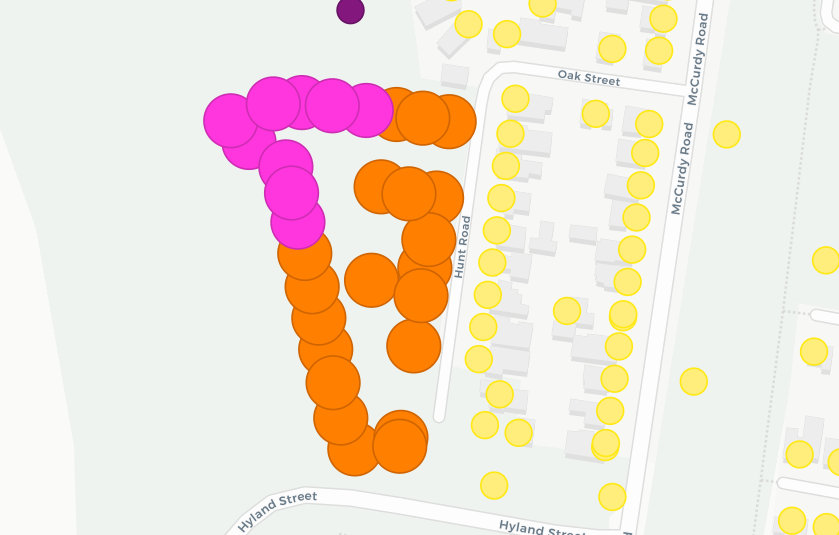

Finally, zooming into the area just to the right of Fyansford – (which is on the side of a hill) – we see this:

Locations on the eastern side of Hunt Road get FTTN – (yellow) – locations on the western side get SATELLITE – (orange) – and just a little way down the hill, locations get Fixed Wireless – (pink).

And just to the north? A purple dot of FTTP.

I mean, what the hell?

Australia will one day rue this shemozzle of a “multi-technology mess”.

Trouble is, that day has already come, and Turnbull should hang his head in shame.